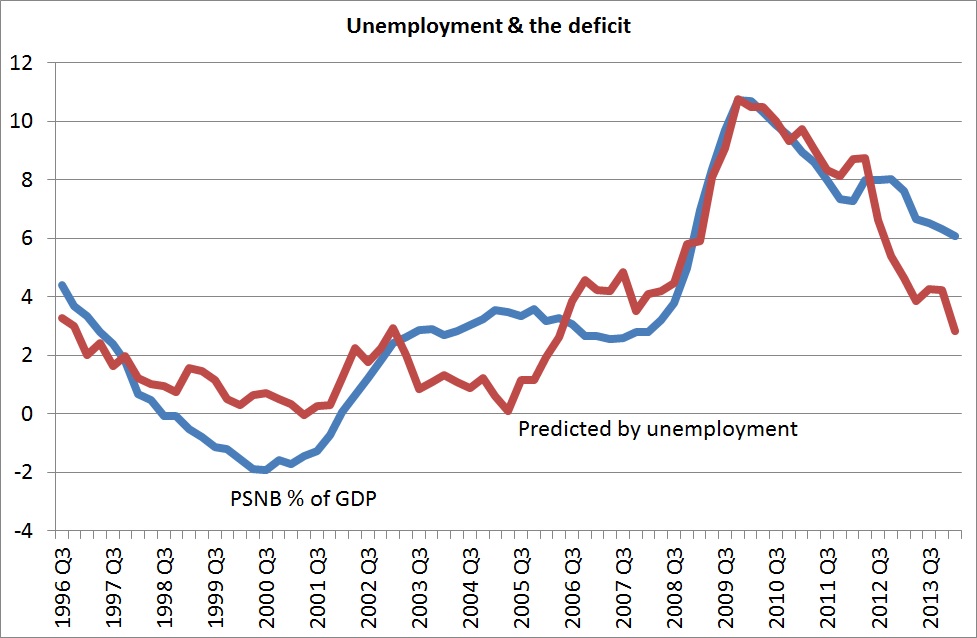

Chris Dillow has a nice chart, plotting the government deficit out-turn against a forecast based on its historic relationship with unemployment, swinging off John Maynard Keynes’ remark that if you look after unemployment the budget will look after itself.

As he says, the interesting bit is what happens after January 2012. Unemployment dropped sharply, but the budget didn’t come in anywhere near as much as you might expect, although it did improve a bit. A gap has opened up. Chris thinks this is a story about productivity.

I half-agree; it’s also a story about the policy-driven shift from unemployment, mitigated by Jobseekers’ Allowance, to underemployment mitigated by Working Tax Credit, aka the bogus hairdresser phenomenon (see here, here, and here). There has been some improvement in the economy, but much of the reduction of unemployment is accounted for by people declaring self-employment with nugatory hours, plus various other fiddles on the Government’s side, like not counting Work Programme attendees or persons under sanction as unemployment. They aren’t earning-out of the tax credit regime, and they aren’t paying income tax, so the budget doesn’t improve.

It’s trivially true that if you aren’t getting any hours, your productivity is zero. Importantly, though, efforts to improve productivity as such won’t help this problem at all, because low productivity is an effect rather than a cause. It’s an effect of policy, but it’s also an effect of the weakness of the labour market, because if the bogus hairdressers were in work they wouldn’t have to find ways to get Iain Duncan Smith off their backs.

How tight the labour market really is may be the most important question in British politics at the moment. Hence Duncan Weldon:

Lot of people urging Ed Balls to be 'Keynesian'. But it's harder to make a Keynesian argument when growth is above trend.

— Duncan Weldon (@DuncanWeldon) September 22, 2014

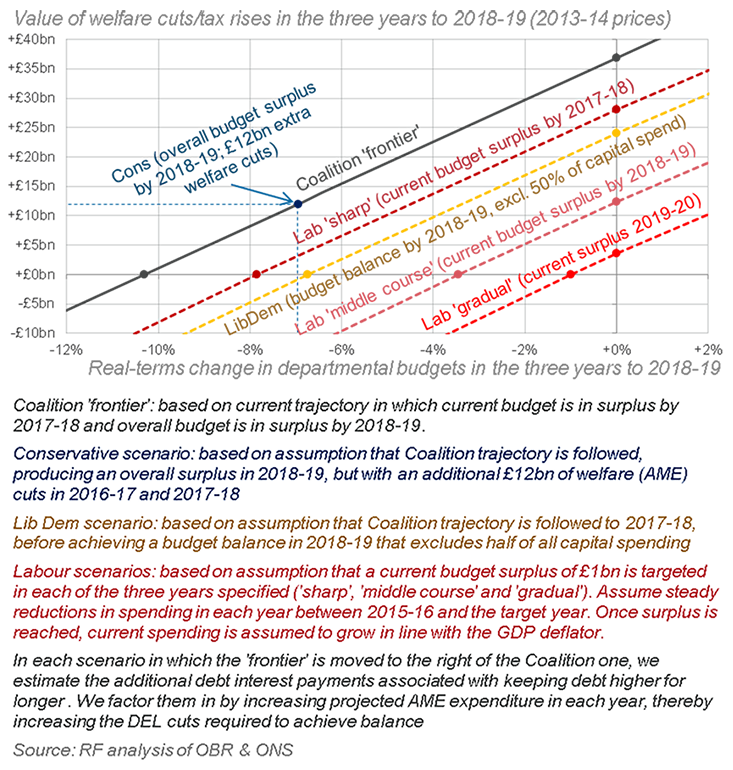

Balls has decided not to offer any new capital investment funded by central government borrowing. In this view, GDP growth is up, and therefore growth should bring down the deficit, and there is no case for fiscal expansion. If there is going to be more public spending there should be more taxation. This shouldn’t be a reason to harrumph off in the corner, though. Resolution did this rather nice chart of the parties’ fiscal plans.

As you can see, before anything else, just going slower is a big, big improvement on Osborne’s plans. Pushing the deadline out to 2019 and finding another £10bn of revenue or savings would allow for a 2% real-terms annual increase for the departments, while the Tory plan requires a 7% annual cut for the departments even with an additional £12bn taken out of social security. And we’re not even discussing Cameron’s giveaway yet, which takes the total cuts in the pipeline to £33bn. Labour would be fools not to run on the Tories’ £33bn cuts bombshell and to repeat the number every five minutes; personally I’m going to bore everyone to tears with it from here to May.

The problem, though, is Chris’s chart; although GDP growth is up and measured unemployment is down, the budget still sucks. And, you know, one in ten young people despair, because they’ve been stuck in the queue since 2007. As the EEF economics blog says, it sucks on the revenue side because income tax revenues are poor, because incomes, i.e. wages are poor. That is, to say the least, not what you’d expect in a tightening labour market.

It might, however, be what you’d expect in a market that is still pretty close to a high-unemployment equilibrium, but one that expresses the insufficiency of effective demand via underemployment rather than unemployment. If we were, that would explain why it is so difficult to reduce the deficit and why wages are so poor, and also why productivity is so poor, via Verdoorn’s law, where productivity gains usually happen when industry is operating at capacity. This is the crucial issue, and I suspect it’s roughly what is happening in France. The risk is that we end up running to stand still, deficit reduction keeps failing because wages and productivity are too low, and the statistics get progressively worse as the low-trust society becomes entrenched.

The good news is that there are some options for Labour investment to go with the absence of more Tory cuts. The public bank plans have evolved, and now foresee National Savings & Investments as its main depositor, which could give it enough welly for quite a substantial capital programme, and you know where I think it should go.

Permalink

Great post. I’ve been getting really tired of economists incapable of conceiving of “underemployment” as a thing and thus bounding off into speculation about new paradigms etc.

Esp. because (e.g. Duncan Weldon) those new paradigms always seem to be about following the austerian path.