Back at the end of 2007, as we dived into the trough of the Great Recession or Great Financial Crisis or Second Great Depression or what you will, a crucial decision was taken. Verizon Wireless, then still a Vodafone division, chose LTE for its new mobile network, and put one of the most important women you’ve never heard of in charge. By the end of that year the contracts were signed, mostly with European manufacturers Ericsson and Alcatel. With that, Verizon declared that the standards wars were over and the alliance between Europe and developed Asia had won. With time it would become clear that Verizon Wireless would also win the first decade of the smartphone era, at least among the American phone companies.

A long term consequence of this blew up just before Christmas when another important woman, Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou, was arrested at Toronto’s airport, dramatizing a slow geopolitical crisis centred on the market for telecoms infrastructure. (This is good on the legals and the point that Trump shooting his mouth off destroys the Canadians’ legitimacy.) The spectacular rise of Chinese industry, the impact of mass mobile Internet adoption, the political realization that information security is a nightmare, the United States’ degeneration into a failed state 50% of the time, Europe hanging together so as not to hang separately – it’s all in this story.

Global worries about Huawei fall into three categories: security, trade, and competition. Each category can be further divided into concerns in good faith and in bad faith.

Ever since Huawei became a major exporter, in the early 2000s, American politicians and security bureaucrats have suggested it is a threat to information security, or security somehow defined.

Some of them, or some of the time, were speaking in good faith. The generally terrifying condition of information security demands a degree of healthy scepticism, especially with regard to a manufacturer from a country where the authorities are completely unaccountable, aspire to superpower status, and also live with a high degree of internal chaos. The alternative suppliers are based in Sweden, Finland, and South Korea; only a naive fool wouldn’t notice a difference in kind between these polities and the PRC.

They also spoke in bad faith. There was a long-standing arrangement between the “five eyes” intelligence allies to each keep an eye on an important network vendor. GCHQ got Nokia, according to Richard Aldrich’s magisterial history of the agency. We know from the Edward Snowden disclosures that the NSA sabotaged shipments from Cisco Systems and tried to influence the international standards processes. It was unlikely to say the least that China would accept anything like this. Huawei’s rise threw a spanner in the works, much as that of the Internet itself had done during the so-called crypto wars a decade earlier. And, you know, it’s in the New York Times:

The National Security Agency breached Huawei servers years ago in an effort to investigate its operations and its ties to Chinese security agencies and the military, and to create back doors so the National Security Agency could roam in networks around the globe wherever Huawei equipment was used.

The security concern led to the trade concern. If you honestly believed Huawei was that dangerous it logically followed that you shouldn’t accept their stuff. By a handy coincidence, if you were worried that you couldn’t spy on them, the same conclusion followed. And if you were worried you couldn’t compete with them, well, a sudden interest in information security also followed.

The issue came to a head in the UK in 2006, with BT’s tender for what it then called 21CN, a major fixed network upgrade. BT astonished everyone by cutting the remaining British vendor, Marconi, out and giving a key element of the job to Huawei. This resulted in short order in Marconi’s sale to Ericsson. The British government was unmoved by this, but it was moved by security concerns both real and cynical.

Its solution was to set up a joint laboratory between CESG, the defensive wing of GCHQ, and Huawei, whose job was to certify the trustworthiness and quality of products Huawei exported to the UK. This can be read as a defensive, trust-but-verify exercise. It can also be read as a veiled version of the five eyes relationships with vendors; CESG couldn’t but learn a great deal about their technology. And it can further be read as a massive vote of confidence in Huawei. Huawei certainly thought so; they openly advertised it and the CTO of their Carrier Business Group said so to my face.

This was a pragmatic solution. It permitted the Chinese to export and the rest of the world to import, offered a degree of assurance that there wasn’t melamine in the baby milk, and served the long term British government agenda of accommodating Chinese ambition. It also built in potential conflict between the Americans and the British; the Americans continued to buy relatively little Huawei equipment (but not none) and give vague indications of doom, the British publicly vouched for it and used it in some quantity. That said, the rather special BT gear turned out not to work very well and nobody there ever wanted to discuss it when I asked.

With two things in their back pocket – CESG’s imprimatur and a massive vendor financing line of credit from two Chinese state banks – Huawei’s sales teams went on a global contract hunt. I remember the CFO of a major African mobile operator saying in around 2011 that he’d built six national networks entirely with their vendor financing. It’s important to note that around this time, credit terms were taking over from price as their competitive advantage.

This is the sort of thing that the WTO is meant to keep an eye on, but it was eventually the European Commission that took action. The Eurocrats suspected that the vendor financing was a disguised subsidy (you bet it was) and alleged that it wasn’t price that was keeping the European vendors out of China. In 2012-2013 there was a trade dispute that ended with an agreement: China Mobile would split up its enormous LTE rollout contract among the vendors, with Nokia and Ericsson getting $2bn each.

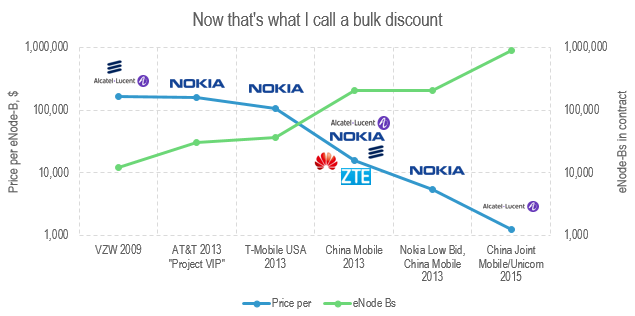

The Eurocrats had a point. By then, Huawei wasn’t the price leader any more. As this old chart of mine shows, prices per base station were falling rapidly as the scale of production rose, and Nokia, now focused completely on infrastructure, was well in the lead of this process.

The telling detail here is that China Mobile didn’t just do the necessary to let the CCP keep the spice flowing. They went back to Nokia Networks for round after round of investment in their LTE network. When Nicola Palmer’s bosses signed with Alcatel in the winter of 2008, they signed for 10,000 base stations. China Mobile ordered 720,000, and then came back for two more rounds of half a million each. This was the revival of a relationship that went back to the 1994 launch of mobile telephony in China. The problem was not that European manufacturers couldn’t compete.

As the industry began to move on from GSM and 3G, there were three and a half options available for how to do that. There was the Third Generation Partnership Project, 3GPP, the follow-on from GSM, with a heavy European and Asian influence. This would be LTE, aka 4G. There was the CDG and CDMA2000, dominated by American phone companies. There was a new, Silicon Valley-led group around the IEEE802 standards community responsible for Wi-Fi. This would be WiMAX. And the Chinese industry was trying to create a further, “indigenous” standard. The acronym you want is TD-SCDMA but the only use this will be is to show I remember it.

China’s Ministry of the Information Industry hoped to boost this when they forced their operators to reorganize into three big groups. China Mobile was ordered to take on the new project and give up the world standard 3G network it was already building under the guise of a “trial”. But it never worked and in any case turned out to involve patents belonging to Siemens. A colleague of mine was told that CMCC was doing it entirely under duress. Meanwhile, 3G was itself a huge disappointment. In the 3GPP world, though, the customers eventually seized control of the project, demanding concentration on pure mobile Internet service, with a much simpler network architecture, and the full international roaming support originally defined in GSM.

Verizon’s decision in 2008 tipped the balance, but the balance would not have been so fine if the North American vendors hadn’t taken some terrible decisions. Motorola hugely overcommitted to WiMAX and assumed CDMA would go on for ever. Nortel did much the same with the twist that its executives also robbed the company enormously. And the global financial crisis turned up the pressure. Either way, by the end of 2009 the Americans were out of the network-building game, the standards wars were over, and the future would be shaped at 3GPP. Silicon Valley firms were some of the first to realise this, becoming major contributors to the process.

But you can’t assume Americans – especially not mercantilists like Trump’s trade representative Peter Navarro, or Robert Spalding, quoted in the NYT piece above, who I think is the guy who proposed nationalizing the carriers and the manufacturers both – particularly like this. If we remember the second, bad-faith half of the security issue, they aren’t going to like that either. Hence, perhaps, the pressure campaign on the other five eyes to do something.

The twist, though, is that the UK’s relationship – even a special relationship! – with Huawei broke down early in 2018, but it was then re-established at considerable expense. This Sydney Morning Herald piece is exciting, but the UK has not banned anything. O2 UK was boasting shortly before its network comprehensively collapsed, ironically because someone at Ericsson forgot to renew an SSL certificate, that it doesn’t use Huawei, but this is far from precise (eg), and 3UK has placed a huge contract with Huawei for its 5G build without anyone stopping them. Politico Europe is good on Huawei’s deepening relationship with Germany but misses that the UK hasn’t banned anyone and has actually taken active steps to fix the relationship up.

At the very core of the original special relationship, Trump’s escalation seems to make the UK cleave closer to the EU and indeed to China. As I said elsewhere, the tragedy of the Brexiters is that they chose the year America resigned from globalization. Trump’s intervention is, in effect, a subsidy to either the European infrastructure builders or the South Koreans – Samsung is doing extremely well in 5G network contracts – and he already declared trade war on South Korea.

Thank you very much for the story. Do you think Ericsson and / or Nokia are in danger of being swallowed up by the Chinese?

No. Both are doing reasonably well – E recovered from its wobbly last year, N won the 4G years as much as any of them did, with the caveat that it’s a low margin biz for everyone these days. I would actually worry a bit more about E as its business model is so heavy on outsourcing/consulting/managed services at a time when the customers want more technical equity and differentiation, also it bungled the media technology stuff and the Cisco alliance (rather like, back in the day, it bought Redback and screwed that up).

Also, I would assume there is a French government veto on N thanks to the Alcatel assets, maybe a German one thanks to the Siemens ones and their new policy on Chinese portfolio investment, and possibly a European Commission one on further consolidation for antitrust reasons.

The one-to-watch is Samsung, which used to be very much second division in infrastructure, but has gained a huge share of the 5G contracts so far, mostly for the weirdo 28GHz stuff but not all.

I wonder if the EU would block the seemingly inevitable Ericsson-Nokia merger.