I originally drafted this post as the second on Tim Shipman’s book last autumn. Having found and re-read it I have revised it, among other things to go with Jonathan Portes’ appreciation for Sir Jeremy Heywood, the signing of a Brexit agreement, and the outing of the American Friends of the IEA

An interesting thought that struck me reading Tim Shipman’s All Out War is that perhaps we should have taken this more seriously all along.

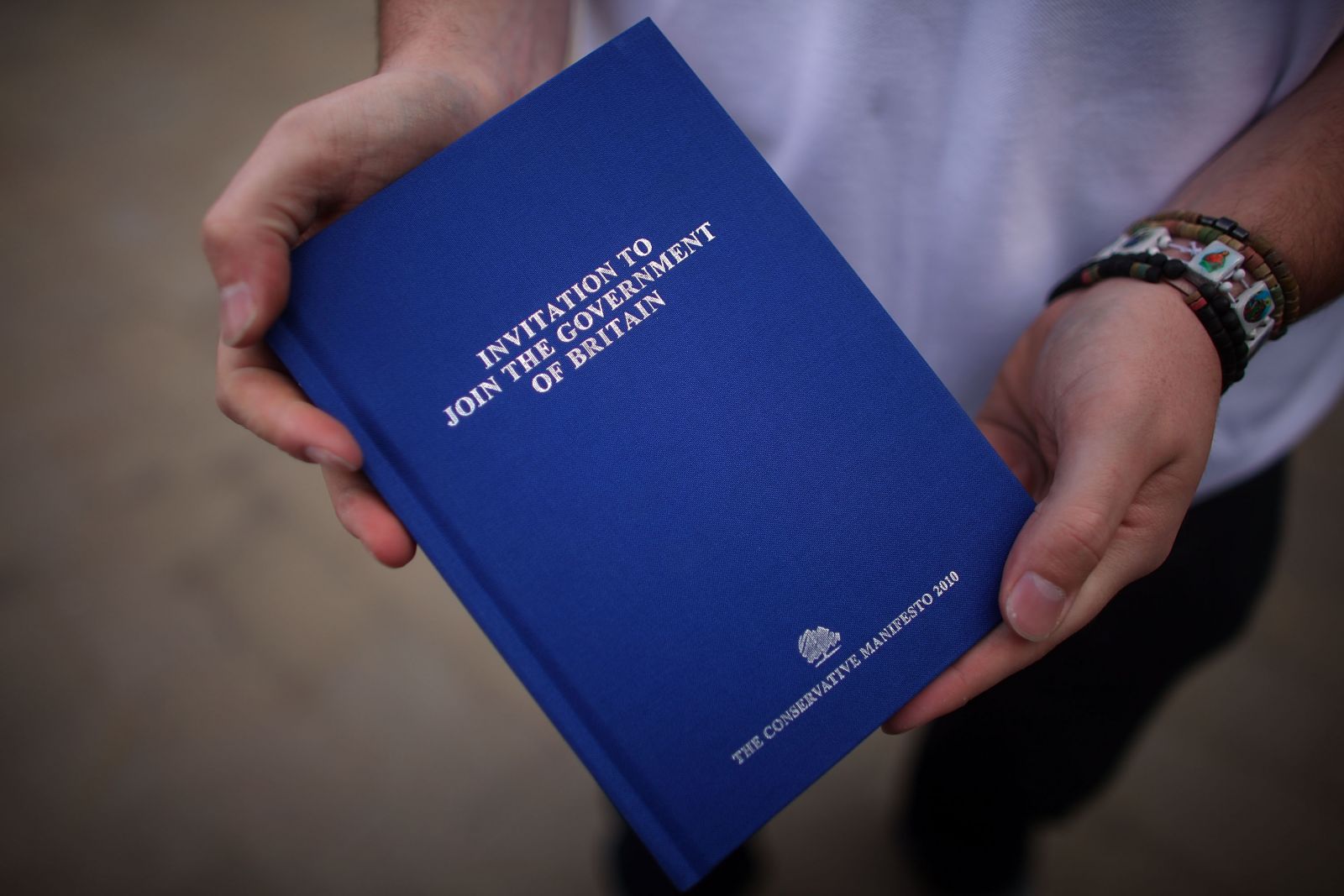

Remember that? David Cameron’s Conservative manifesto from 2010, titled Invitation to Join the Government of Britain. This was widely seen as fluff at the time, and in so far as anyone cared, they stopped caring as the Big Society initiatives ran into the sand in 2011 or thereabouts. Perhaps, though, its soft-libertarianism and suspicion of the institutions was an important preview of how Cameron would approach the defining challenge of his premiership.

Cameron repeatedly adopted the style tropes of Tory Euroscepticism to get ahead, and then countermarched when he had to function as prime minister. This process worked as long as he retained enough authority to ignore the Eurosceptics. While there was still a belief that either the Big Society or the austerity programme would work, he had it. By 2013, though, the first was forgotten and the second in real trouble. A critical mass of Tories had developed who thought George Osborne, and by extension the prime minister, had promised the earth on economic policy and failed to deliver.

Cameron, as a rule, approached political problems with two solutions in hand. It was either the shotgun, or the golden retriever; the smooth PR man or the crimson tide. Short of ammunition to deal with them, he therefore chose the retriever solution in offering them a referendum, and decided to outbid anyone else who might be offering by making it a sudden death, in or out proposition. The tail was now wagging the dog to an unprecedented degree.

This committed him to trying to renegotiate the terms of British membership in the EU. We saw in a previous post that the biggest problem here was that Tory Euroscepticism had never defined what its grievance against the EU actually was. As a result, neither Cameron nor anyone else could formulate a coherent negotiating position. But that’s not what I’m interested in here. The legacy of the Invitation to Join made itself felt in technique rather than content, in the tactics, not the strategy.

I’ve pointed out before that a major but under-discussed theme of the Cameron years was that the civil service was an enemy. Clement Attlee saw it as the instrument by which he would build social democracy. Margaret Thatcher saw it, although in a different role, as the means by which she would build Thatcherism. John Major wanted to fundamentally change its structure, and the changes he did make have had enduring consequences. As far as I can see it has only been Cameron who wanted to diminish it, replace it, or banish it, by breaking up the role of Cabinet Secretary, creating a new job of CEO, and staffing up from the private sector or really from the thinktank world.

To a large extent, he pursued renegotiation using advice he got from personal friends and special advisers, and he tried as late in the day as possible to exclude both the Foreign Office and the Cabinet Office European Secretariat. All Out War, notably, centres this so-called chumocracy in its narrative. It was an invitation to join the government, but it wasn’t offered to just anyone. Now, though, I increasingly think it was even more a thinktankocracy. The key individual was Mats Persson from Open Europe – it’s worth remembering that this organization is a rebranded version of the late 90s anti-Euro campaign machinery, and also that Persson found himself a well rewarded billet with Ernst & Young consulting on the problem he himself created.

The key tenet of Persson’s diplomacy, of which he had exactly no experience, was that only Germany mattered. The European institutions were of no interest and neither were other European powers. You could go further and say that Cameron and his core group of staffers reduced their diplomacy to the statement that only Angela Merkel personally mattered.

Among other things this meant throwing overboard the policy Cameron and William Hague had followed up to this point, which emphasised relations with the new member states and also with Northern Europe. This really wasn’t a bad idea, as the Juncker Commission is heavily Nordic. But this now went by the board in favour of an obsession with trying to charm Merkel.

One of the most embarrassing bits in the book details David Cameron’s personal diplomacy towards Merkel. This was the golden retriever policy on an epic scale, reflecting Cameron’s conviction in his personal capacity to persuade, a déformation professionelle to be expected of a PR man turned politician. But – time and again – he ballsed it up grossly. Having gone all in on the politics of the personal, he has to take personal responsibility for this.

What they above all wanted was some sort of understanding with her that could be legitimised by the European Council, over the head of the Council of Ministers, the Commission, and the Parliament. This was, of course, the same scheme Yanis Varoufakis was pursuing around the same time. The core idea was that there would be an all-night summit and eventually they would get her to crack and agree to…something.

Some of them still think this would have happened had it only come to that, and some of them even briefed Tory donors it would be “a trading relationship”. That it already was clearly escaped them, as did any idea of what that meant. We still see this in ideas like “managed no deal” or “mini-Brexit”, where the UK and the EU would supposedly sign a succession of agreements to keep things working on a technical level. For this to work, their totality would have to be something like at least the current withdrawal agreement draft.

This, however, was an insight that had to come from the reviled professionals. No progress was made on anything until the European secretariat was transferred back to No.10 in the autumn of 2017. By this time, the project of cutting the civil service down to size had long since run into the sand. Bit by bit, Jeremy Heywood pulled back together the authority Cameron had wanted to disperse. The institution’s survival, and indeed triumph, is his epitaph.

However, with time, the fingerprints of the original project become more obvious – this outstanding blog post on the 55 Turton Street factory for fake thinktanks is a case in point. Perhaps we should understand the Cameron years as a project to replace Whitehall with K Street.

two solutions in hand. It was either the shotgun, or the golden retriever; the smooth PR man or the crimson tide

I’m a bit hungover and untogether atm, so when I stalled on this sentence I thought it was me. Two re-readings later I’m still stumped. What’s, or rather what are, the references?

The image is Cameron as a posh sportsman (which he is) with the classic equipment – a shotgun, and a golden retriever. But Cameron also oscillated between the two poles, being a smiley, waggy retriever or else having outbursts of junker arrogance (listen to the doctor). Also, he used to go red in the face when anyone asked him a difficult question and Labour twitter referred to this as the crimson tide

Cameron was a believer in Yes Minister, by which I mean he agreed with its story of the Civil Service having its own agenda and manipulating and sidelining ministers. So sidelining the Civil Service and replacing it with K street sounds quite believable.