This BBC Scotland story about a swimming pool in Helensburgh should probably have got much more play than it did. Perhaps it was something about the framing? It’s a pity, because the central thrust of it is really important to the future of the polity.

Back in the autumn of 2015, when journalists rejoiced in cutely nicknaming George Osborne “Cx” after an internal Treasury abbreviation, it was a commonplace that he was “the most political of Chancellors” and that this was a good thing. Another way of putting it would be that he had imported the American tradition of pork-barrel politics into the UK and delighted in doling out goodies to people he hoped would vote for him. The swimming pool in Helensburgh is a case in point – that fair city got £6m in central government funding for it, and importantly, it got the money outside the usual Barnett formula accounting, as a purely discretionary executive gimme. We could also recall the famous codger bonds and their slightly less famous letter.

All politicians try to do this, up to some point. Why was this significant?

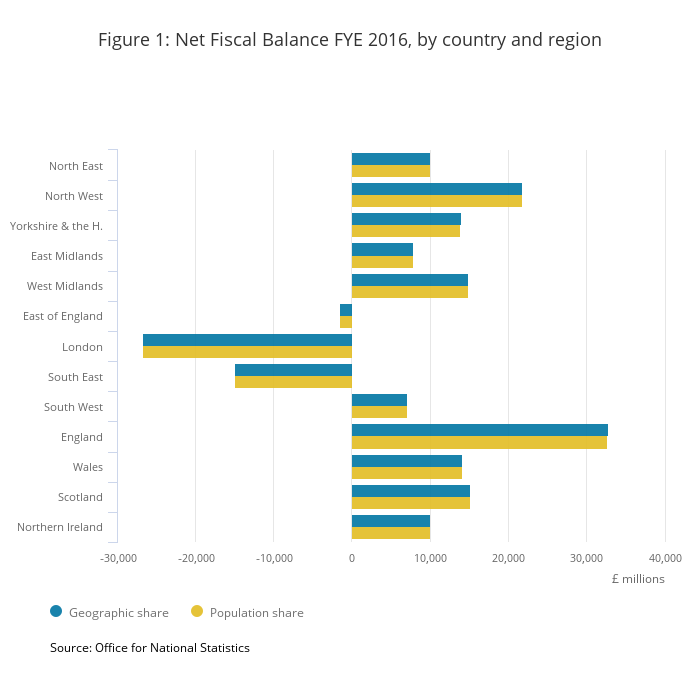

Most countries have some sort of formalised process to decide on fiscal transfers between the central government and local governments. Some, like Germany, institutionalise this in a process. Others, like the United States, put it explicitly in the gift of elected politicians. The UK, characteristically, opted for a fudge managed by the civil service. This was fudge on a scale the National Trust couldn’t match – it’s only now, in the year of Our Lord, 2017, that the Office for National Statistics has even started to maintain a data series that tracks regional fiscal balances.

As usual with such things, this worked so long as nobody pushed their luck. Then, George Osborne pushed his luck.

Osborne tore up the discreet understanding in two ways. First, he radically shrank the pot. No branch of government has had a bigger contribution imposed on it than local government. By 2020, funding to local government will have been cut by 77% and a majority of councils will be getting absolutely nothing. Having intensified the struggle over resources, he then cranked up the electoral use of discretionary Treasury expenditure. The Caledonian Sleeper got £50m, and led the wretched front page of the Guardian. Helensburgh got its swimming pool. The codgers got their 4% bonds…right up until they got railroaded into rolling them over at next to zero rates! Ha-gotcha!

One of the side-effects of this is to destroy trust in the institutions – because what can they do for you? – and instead to advertise the possibility of getting a special deal, a swimming pool. Because the inner workings of the system were never made explicit, it’s also very difficult to oppose it. The tyranny of structurelessness is at work, the issues themselves are dull and complicated (hey – admit it, you’ve not read this far!), and the fact that councillors are personally legally liable to deliver certain services makes them into human shields for the central government.

I see this as part of the broader trend I discuss in this A Fistful of Euros post. Populism is among other things the rejection of method coupled with the repoliticisation of the sovereign. This is suited to the low-trust society, but perhaps it’s also an effort to create it. I would argue that the UK’s populist experience has been the period since 2010 – we may think we’re waiting for the barbarians, but in fact they were here all along. You might even say: they are us.

Edit: added link to Jo Freeman essay on the tyranny of structurelessness

To relate this to your NHS post, part of the problem with the Dillow anarcho-syndicalist faction “against managerialism” is how it implicitly endorses structurelessness and low trust.

I agree with most of what you write about these subjects. The question is, though: why is “method” being rejected?

Presumably “method” isn’t delivering for a lot of people and the level of accountability in “the method” is too low. About 25 years ago, I had a conversation with Phil Gould and realised that New Labour was focused almost completely on the feelings of a small number of swing-voters in marginal parliamentary constituencies; and I wondered what would be the result of a focus on such as narrowly-defined group of people.