Andrew Gordon’s The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command is pretty special. In essence, this is a deep history of a mentalité, a way of thinking and seeing, and it’s a history that spirals outwards from a very specific time and place and a very specific artefact.

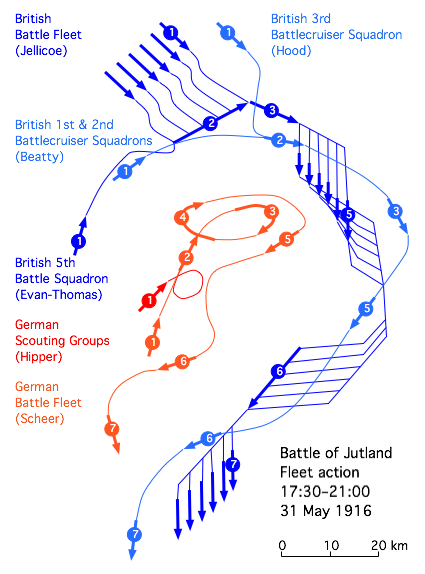

The time, the place: Windy Corner, a specific but only roughly defined bit of the North Sea that existed in reality for about 15 minutes from 1815, British summer time, on the 31st of May 1916, and for many more years as an purely spectral object of historical inquiry, after-action operational analysis, and cynical self-justification. That was the name given to the chaos ensuing as the British fleet deployed from column into line and the destroyers, cruisers, and battle cruisers tried to keep out of its way and each other’s, under fire. It’s just south of marker 2 on this chart from Wikipedia.

The artefact would be an Inglefield clip, a gadget for hanging signal flags on their halyards quickly invented in 1895 and still in use today. Again per Wikipedia:

An artefact is an ideology. In this case, the clip embodies the Royal Navy’s doctrine of command of the time. This was implemented in the technology of signalling, like the clip, the flags, and the codebook, and jealously guarded by a powerful career mafia of signals specialists, who both gave the ideology its political punch, and were themselves shaped by it.

The content of this ideology was drawn from a wider culture. It incorporated what is known in German as Befehlstaktik – the idea that leaders set down their detailed, specific instructions in written orders which followers execute without interpretation – and a looser idea of hyper-obedience which Gordon roots in a certain idea of manhood based on a revived ideal of chivalry. He argues that this ideology, so drastically different from the practice of Nelson’s time, succeeded because it permitted the RN to adapt to the Industrial Revolution. The freedom of manoeuvre steam power provided, and the changing mix of trades aboard ship, would be channelled into a tactical doctrine that let commanders manoeuvre as if on a parade ground, by incredibly detailed signalling.

The defenders of the ideology were also very interesting. The book is in part a group biography of key players. Gordon notes that their careers had key elements in common, and that in fact these elements were common across the signalling specialisation. Those were Royal patronage, Masonic networking, neochivalrous culture, and weirdly, association with the Royal Geographical Society. Less weirdly, RUSI also played a big role. Scandals involving the princes serving with the Navy frequently seem to have helped the men involved progress in their careers, not least because a flag lieutenant’s job included acting as a social secretary for the admiral, and quite a bit of celebrity management was all in the day’s work. Also, a ridiculous number of people in real jobs in 1914 had spent most of their sea time in the Royal Yacht.

Before we drift into laughing at quaint Victorians – and if that’s what you want, Gordon can deliver in spades, this book is packed with seriously weird characters and the pen-portrait footnotes can be brilliant – it’s worth pointing out that efficient modernising technocrats didn’t exactly help. The new signal book was itself a product both of the new technology of steam power, and of the new science of comparative linguistics. It was literally designed as a language. Also, there were complicated links between the development of analogue computing fire-control and signalling.

The effect of radio was ambiguous. Although officers whined about having to listen to signals from London, they were the same people who fervently believed it was literally better to lose the ship and everyone in her than to turn a blind eye to a signal. Also, where the signal book encouraged verbosity in tactical communications, radio encouraged it in administrative and strategic communications. Gordon points out that in some ways the real revolution in radio was the move from radiotelegraphy to voice radio; W/T was closer to e-mail, while voice was immediate.

There was always opposition to the signals culture. In part this was inevitable due to its role as a mafia for career advancement; its members couldn’t help making enemies as they scrabbled up the hierarchy. But in part it was rooted in deep scepticism that the incredibly complicated manoeuvres, lengthy hoists, and huge teams of professional signalmen would ever be practical in war. Gordon brings us George Tryon as a sort of John Boyd figure, who proved it was possible to do better with a vastly simplified but therefore more expressive signals language, and by delegating much more responsibility to ship’s captains and squadron commanders.

This brings us to the fateful accident when Tryon cocked it up and collided with his second-in-command’s ship. The 2iC argued at the inquiry afterwards that his duty was to obey whatever flag was hoist, even if it meant ramming the flagship. It didn’t matter that Tryon had been operating under the standard signal book at the time, not his tactical code. A fairly shameful cover-up – another – was organised, and the ideas went down with the man. The future would be Tryonite, but the RN would have to learn it the hard way.

One reason why the opposition failed was that the establishment was such a diffuse concept. The school of signals in Portsmouth, which gave it the apparatus of a profession, such as exams, credentials, a hallowed home ground, and a leader, was founded quite late in the day. Without it, they benefited from the tyranny of structurelessness – it’s difficult to criticise something that has no official existence.

I sometimes wonder if battle diagrams themselves – esp. of Trafalgar – corrupted the sense of what it meant to be in charge of a naval engagement like this. On paper it starts to look like you can exercise close control…

Since I’m not much of a german military buff, ‘befehlstaktik’ was a new term to me.

But, googling around, I was surprised not to immediately find a mountain of opinion pieces comparing it to software development.

[I’d imagine Befehlstaktik as either waterfall or process-based management. Then you can reimagine Auftragstaktik as a kind of Agile. Full of sprints — though the scrums would happen whenever you find a bit of cover, and be less ‘stand up meetings’ than ‘keep your head down you idiot’]

Anyway, there is for sure a lucrative consultancy career waiting for whatever underemployed history buff can scrape off enough of the germanness to make it saleable.

Permalink

Gordon’s book is fascinating, but he misses an important bit about the context of the battle. At the start of the war, the German assumed that the British would start a “close blockade”, hovering outside the German ports to attack the German fleet as soon as it showed itself, just as Nelson did outside Cadiz before Trafalgar. Since coal-fired ships needed to refuel in harbour frequently, the Germans expected to be able to pick a moment to sail out with their entire fleet, overwhelm the part of the British fleet that was on station, and thereby have won the naval war.

But the British didn’t do that. They parked their fleet in Scapa Flow, hundreds of miles away, but close to where the German fleet would have to go if it was to reach the Atlantic. The minefields in the English Channel were trusted to keep the Germans from going that way, and they conceded the point by never trying it.

The Scapa Flow plan made sense because of radio: the British could keep destroyers and submarines off the German ports as lookouts, who would report any German sorties, giving the British fleet plenty of time to raise steam and intercept the Germans, at full strength. Like most good strategies, it works even when the opponent figures out what’s going on.

That bit of strategic use of radio is obscured by the British gaining access to the German codes after the start of the war, thanks to the Russians, but it was a sound plan and would have produced much the same result whenever a battle took place. The German fleet was ineffective for war purposes.

The Royal Navy certainly had some tactical off years around 1914-15 (which Gordon splendidly explores). But what stands out is the speed with which it assimilated new technologies before the war, planned and redeployed to meet a new strategic challenge (eg handing over the Med to the French and concentrating on the North Sea), and updated tactically through the war. The RN should be on everyones management list, as staying top of a rough game for two centuries is an outstanding record.